Losing a parent can make you resilient, but resilience can morph into hardness

OPINION: I have to dig deep to show emotion when a friend's upset. Adult tears are mesmerising.

It's not that I don't feel their sadness, oh I do. It's just that I had to cope with intense grief as a child.

I was 11 and Dad was supposed to live forever. Losing a parent when you are young can make you resilient in many ways. Over time though, resilience can morph into hardness.

It's taken years of watching the close bond between my husband and his dad to realise a father's role doesn't diminish at the end of childhood. That bond was what pulled my husband, and our young family with it, back from Auckland to New Plymouth last year.

There were a number of reasons for this move, but most pressingly has been my husband's need to spend quality time with his father before age and ailing health rob them. Through seeing my husband snuggle up to his dad like a boy and ask him for advice, I've learned that the role of a father is one intended to guide us throughout our lives.

Dad, Mr Lotter as New Plymouth's Spotswood College students knew him, moved to Otago to start a new life after my parents' separated. I last saw him on Christmas Eve. He planned to surprise us with a visit the following Easter.

The lung cancer surprised all of us. I was sheltered from the seriousness of Dad's smoking habit, which he had promised to quit when my little sister stopped sucking her thumb. It was a bit of an unfair competition to have with an 8-year-old.

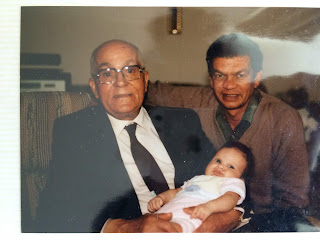

This year marks 20 years since Dad's death. He's been gone from our lives twice as long as he was a part of it. He would have known nothing of my intentions to become a journalist, though maybe he had an inkling.

One of my last memories with Dad was when we were at his new computer. He asked me what I would ask then-US president Bill Clinton. Because, did I know, he was just an email away? I tried deflecting so Dad would stop playing around with his new Microsoft Windows programme and let me get on with playing Rodent's Revenge.

"How about, why do Americans all show-off?," 10-year-old me answered flippantly, hoping he would drop it.

"Yes! Why do American's show-off?" Dad was delighted. "Write it! Why do American's show-off? Send it!"

While Mum tends to be the one who assures me my best is always good enough, I reckon Dad would still give me the proverbial kick up the bum. Like he did when I tried a spicy recipe from his beloved homeland South Africa, when we were kids. My sister couldn't hack it, but I charged on, wanting to impress him. "Go for it!" he cheered.

I'm sure this would have been his phrase of choice when feelings of homesickness and lack of confidence threatened to thwart my career before it had really begun. "Go for it!"

When I was tentative about accepting the lifestyle reporting role I'd been hanging out for because the salary wasn't as much as I'd hoped. "Go for it!"

When I submitted my writing for an industry award and ended up winning it. "Go for it!" He would have gotten drunk on celebratory wine too, and partied with the best of them. And who might have urged me to fight harder for my career when the idea of returning to work lost its appeal when my oldest son was born. "Go for it!"

In those early days with my newborn, Mum hesitated to tell me who she thought he looked like. She worried that in my hormonal state, the reminder of Dad would upset me. But I had already noticed those signature serious eyebrows, the jubee lips, the rounded jaw. A beautiful little boy in my Dad's image.

I've dealt with Dad's loss. With my husband, son and mum by my side, I travelled the earth to connect with his family, who until two years ago we had not met. We have laid his bones to rest.

But I still have moments where I feel disappointed. That maybe if he had a glimpse of the life that lay ahead, Dad might have fought harder for it. As an 11-year-old, it didn't make sense that he was gone. He was far too alive to be dead.

My son, now 3-years-old, tells me he'd like his Oupa around.

"He's in heaven," I gently explain. "You have your Granny, your Grandma and your Koko."

"I know," my boy says. "But I still need my Oupa."

I know, I think. I do too.

Michelle Robinson is a New Plymouth-based journalist specialising in lifestyle issues. When she's not writing, you can find her reading on the couch with her two young sons.

Stuff

It's not that I don't feel their sadness, oh I do. It's just that I had to cope with intense grief as a child.

I was 11 and Dad was supposed to live forever. Losing a parent when you are young can make you resilient in many ways. Over time though, resilience can morph into hardness.

It's taken years of watching the close bond between my husband and his dad to realise a father's role doesn't diminish at the end of childhood. That bond was what pulled my husband, and our young family with it, back from Auckland to New Plymouth last year.

There were a number of reasons for this move, but most pressingly has been my husband's need to spend quality time with his father before age and ailing health rob them. Through seeing my husband snuggle up to his dad like a boy and ask him for advice, I've learned that the role of a father is one intended to guide us throughout our lives.

Dad, Mr Lotter as New Plymouth's Spotswood College students knew him, moved to Otago to start a new life after my parents' separated. I last saw him on Christmas Eve. He planned to surprise us with a visit the following Easter.

The lung cancer surprised all of us. I was sheltered from the seriousness of Dad's smoking habit, which he had promised to quit when my little sister stopped sucking her thumb. It was a bit of an unfair competition to have with an 8-year-old.

This year marks 20 years since Dad's death. He's been gone from our lives twice as long as he was a part of it. He would have known nothing of my intentions to become a journalist, though maybe he had an inkling.

One of my last memories with Dad was when we were at his new computer. He asked me what I would ask then-US president Bill Clinton. Because, did I know, he was just an email away? I tried deflecting so Dad would stop playing around with his new Microsoft Windows programme and let me get on with playing Rodent's Revenge.

"How about, why do Americans all show-off?," 10-year-old me answered flippantly, hoping he would drop it.

"Yes! Why do American's show-off?" Dad was delighted. "Write it! Why do American's show-off? Send it!"

While Mum tends to be the one who assures me my best is always good enough, I reckon Dad would still give me the proverbial kick up the bum. Like he did when I tried a spicy recipe from his beloved homeland South Africa, when we were kids. My sister couldn't hack it, but I charged on, wanting to impress him. "Go for it!" he cheered.

I'm sure this would have been his phrase of choice when feelings of homesickness and lack of confidence threatened to thwart my career before it had really begun. "Go for it!"

When I was tentative about accepting the lifestyle reporting role I'd been hanging out for because the salary wasn't as much as I'd hoped. "Go for it!"

When I submitted my writing for an industry award and ended up winning it. "Go for it!" He would have gotten drunk on celebratory wine too, and partied with the best of them. And who might have urged me to fight harder for my career when the idea of returning to work lost its appeal when my oldest son was born. "Go for it!"

In those early days with my newborn, Mum hesitated to tell me who she thought he looked like. She worried that in my hormonal state, the reminder of Dad would upset me. But I had already noticed those signature serious eyebrows, the jubee lips, the rounded jaw. A beautiful little boy in my Dad's image.

I've dealt with Dad's loss. With my husband, son and mum by my side, I travelled the earth to connect with his family, who until two years ago we had not met. We have laid his bones to rest.

But I still have moments where I feel disappointed. That maybe if he had a glimpse of the life that lay ahead, Dad might have fought harder for it. As an 11-year-old, it didn't make sense that he was gone. He was far too alive to be dead.

My son, now 3-years-old, tells me he'd like his Oupa around.

"He's in heaven," I gently explain. "You have your Granny, your Grandma and your Koko."

"I know," my boy says. "But I still need my Oupa."

I know, I think. I do too.

Michelle Robinson is a New Plymouth-based journalist specialising in lifestyle issues. When she's not writing, you can find her reading on the couch with her two young sons.

Stuff

Comments

Post a Comment